The Neotenic Experience in Groupanalysis: Species Creativity Through the Group, the Body and the Imaginary

Reviewing the evolution of the sapiens species, it is interesting to note how the definition of Homo sapiens sapiens finds the reasons for its success in culture.

Yet the study of man, of the Sapiens sapiens species, immediately poses an internal conflict of observation and self-observation on the nature-culture axis.

At the same time, it seems impossible to exclude variables and/or historical, social and anthropological references. In this multidimensionality of observation planes, the Sapiens Sapiens species is therefore faced with a paradox or perhaps a uniqueness of observation and study that can only be studied through a complexity paradigm.

The scientific-cultural framework from which I intend to start refers back to the paradigms of modern neurobiology and psychology characterised by an anthropological verification (knowledge of man) onto which the various epistemologies on human nature are projected: biological, cultural and mental. The multiple knowledge of man as an object of knowledge concerns man understood both as Homo sapiens and as a person irreducible to any exhaustive categorisation (Menarini R., Marra F., 2015).

The structural implications of this approach are characterised by four fundamental variables inherent to neuropsychology and neuroscience: organism, environment, subject and object. These variables seem paradoxically to be ntegrable insofar as the relations between organism and environment seem to be unable to disregard a biologisation of the mind, while the subject-object one refers to a purely mental dimension, i.e. nomopoietic.

This is the concept of the self-referentiality of mental structures, in the sense that they can only have themselves as a reference.

For Maturana (1985), poiesis is distinguished from praxis as a specific dimension of the autonomy of the creative process. Autopoiesis and self-referentiality are responsible for the impracticability of an objectivisation of the mind only with reference to an extramental context such as the neurophysiological or sociocultural apparatus.

It is therefore necessary to analyse the brain, culture and mind from a multidimensional perspective. The introduction of specific epistemological paradigms, taken in terms of independent variables, allows us to have a biopsychosociocultural dimension and field view.

I would start with neurobiological science, which takes brain structures as independent variables; then anthropological and sociological science, which takes culture as a variable; and finally the basic psychological science of gruopoanalytic dynamics, which takes the inner world, which can be understood as the relationship between subject and object, as an independent variable. The comparison between these variables, when carried out in the direction of the psychic sphere, is based on the study of the biopsycho-cultural basis of mental functions.

I believe that group-analysis, as a method and intervention (psychotherapy) and as a complex model of the study of the human, responds to this paradigmatic setting and places us scholars and experts in dialogue with other disciplines to address certain themes and reflections.

In this Summer School, what really stimulated me was to start from the title and imagine/interpret it as an invitation to complexity. TrasformAzione recalls to me the principle of EGO-training in action and also field theory as well as an association to the imaginary and creativity through dreams and through the body.

As personal as this reading may be, I would like to share it with you.

First of all I would start with transformation. Needless to say, the experience through the group is necessarily transformative, never taken for granted at the same time.

There is no session that is not full of potential novelties and rehashes with time and space in a continuous becoming. Yet in some fixations or regressions, where one believes that there is a suspended and immutable time, here is a dream, here is a memory, here is an association that reactivates or reworks or diverts -to find other paths- the movement and the underlying or emerging mental/affective process.

This is, in my opinion, the dimension that we can define as neotenic (or creative) that characterises man and group at the same time.

I began by emphasising the question of culture in relation to the species Sapiens Sapiens. Well, several authors have rightly posed questions on, for example, mental disorders and culture. Ernesto De Martino recalled how Biswanger had hypothesised that the limit of Freudism consisted in a reduction of man to nature, as a result of which man is the evil that society and history strive to combat. Culture is the mask and psychoanalytic theory unmasks its drive roots. But the weakness of Biswanger’s hypothesis lies in the fact that the drive life, to which Freud refers, also places the biological and the cultural together. But if one introduces the dilemma of the nature-culture relationship, one comes to the conclusion that it is nothing more than a system of removal underlying the very emergence of the unconscious: the birth of culture and primary removal (Menarini R., Marra F. 2015) . On the other hand, George Devereux (1978), in polemic with the culturalists, maintains that the unconscious is composed of two elements: the psychic representatives of the ES (drives) that have never been conscious and what was initially conscious but was subsequently removed.

At the level of cultural pathologies, only the removed material of the conscious order is taken into account, which Devereux divides into two groups:

The unconscious segment of the ethnic personality;

The idiosyncratic unconscious structured with reference to personal experiences especially of a traumatic nature.

According to this model, the first group comprises the cultural and non-racial unconscious (e.g. Jungian archetypes). This is the ethnic unconscious that relates to an individual’s entire culture or cultural unconscious, consisting of everything that each generation learns to remove according to the basic demands of the culture. The result is the emergence of common unconscious conflicts. This is the negative identity (Menarini and Lionello, 2008) in terms of the cultural double that produces the typical situation of alienation characterised by four basic elements:

Dissociative Identity Disorder.

Dissociative Fugue.

Split between personality and cultural identity.

Confusion in the area of existential meanings.

Dissociative Identity Disorder is the result of the failure to integrate the various aspects of identity, memory and consciousness.

On the other hand, Marc Augé proposes research and entographic models as a reading of cultures, the so-called three ethnologies. These are models of observation and application to the interpretation of human relationships through ties and places. I feel it is relevant to recall them briefly from a complexity perspective as I believe that every group session more or less consciously applies these three dimensions, which are connected with the experience of time, space and the individual/group. In fact Augé states that the three ethnologies are precisely that of the path; that of the stay; that of the encounter. I assume that the Summer School has this intrinsic and epistemological value within it and in its well-founded if ‘transient’ myth. Places, cultures, religions, but above all Group.

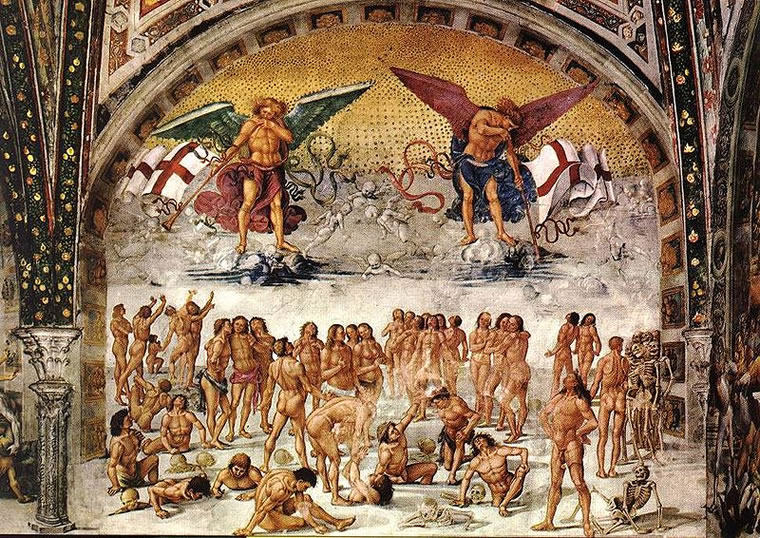

It is equally true and evident, however, that in a destructured and alienating dimension in terms of the cultural double, the group becomes a neotenic and foundational space insofar as it is a transformative instrument capable of responding precisely to this potential dimension of negative identity (picture 1)[1].

According to Lacan, neoteny is that evolutionary mechanism, typical of the sapiens species, characterised by a specific prematurity since the birth of man. From our point of view, the neotenic phenomenon can be understood as the maintenance of foetal and neonatal traits (related to the development of the mental) in adult life.

Neoteny is thus that relational dimension that links the biological register as well as the mental and cultural register. The group as neoteny encompasses within it – as a container – the three ethnologies in terms of space, time, gruppality, i.e. path, sojourn, encounter. The neotenic factors are five (Nucara G., Menarini R., Pontalti C., 1986; Menarini R., Neroni G., 2022, 2010; Agresta D., 2022) and have a dynamic and evolutionary/transformative function and are structure at the same time.

They are:

1. Physical-morphological aspect: in particular, fetalisation. As a process characteristic of neoteny, it concerns the preservation of distinctive aspects of one’s own foetal phase as well as ancestral foetal traits, the latter being retained in the development of adults of a descendant group.

2. Delayed development: human development is extremely slow compared to that of other animals, resulting in a prolonged infant phase and consequently an equally prolonged family dependency.

3. Slow brain development: it should be noted that the human cranial sutures do not finally fuse until the age of 20. The human brain therefore grows and increases neuronal interconnections. This entails a long learning period.

4. Family group: on the basis of the preceding neotenic factors, it follows that the human baby needs to be cared for and protected for a long time, otherwise it could not survive. The family provides a neotenic space within which the man-child can find care and warmth and can acquire the psychic and material tools to live and adapt to the world.

5. REM dream: this is a neotenic factor since in the foetus it occupies the whole of sleep while in the adult it represents a continuation of this foetal sleep. The human mind would use REM sleep as a psychic organiser with an important creative and plastic function and as a possible link between conscious and unconscious aspects of the human psyche.

Neoteny is therefore considered a matrix as it establishes a common form emerging from the biological, the mental and the cultural.

In this multidimensionality through the group, the experience of the body and its constitution as a relational and imaginative experience and as a connection in the processes of mentalisation by means of oneiric representations and associative work in therapeutic groups is posited as a connection.

Here again a complex and unique field emerges that can only be referred to the sapiens species.

The problem of the body in my opinion characterises the study of the therapeutic group as much as the dream world and the constitution of the mental field as a representation of the founding myth of a therapeutic group. Both aspects (soma and/or psyche) -what we can define as ‘group-analytic psychosomatics’-, determine an inter-correlation between the parts and between the dimensions of the field where it is relevant to link the intrapsychic conflict with the soma and the contextual reality. But in neotenical terms the body, whether real or metaphorical, acts as a connection and link between group members. It seems to me that the body of the group can represent the body of the dream and vice versa and thus a fundamental step in terms of desomatisation with respect to the process of mentalisation and the relationship with the formation and expression of the imaginary.

According to Kaes (2002): ‘the psychic space of the groups in which dreams are produced and narrated is itself already a dream space. Widening the field, we can consider that this oneiric part of the group is nothing more than a version of the oneiric foundation of the intersubjective bond’ (p. 81).

In my opinion, it seems to me that Anzieu D., has been able to suggest an interesting reading that we will develop later on the relationship between group, body and dream. This thesis between the group and the dream allows us:‘ to understand that the structure of the group and the dream, their psychic spaces, under different forms, are spaces of the oneiric imaginary’ (ibid, p. 81). The group is like the dream because it is the place for the realisation of unconscious desires and the manifestation of the effects of the unconscious. ‘The group is a space of dream, and of fantasy, a place of illusion and the illusory. But more precise is the idea that group (but also couple and family) bonding requires that a common and shared space be constituted: the members of a group communicate through their oneiric ego (Guillaumin) and this is how the oneiric matter of the group is formed’ (ibid p. 82).

In fact, in the group or in the dream and through the body (imagined or acted) there is the passage to an ethnology of the encounter that has already gone through a path (dynamics) and of sojourn, that is, the constitution of a historical field and a present field that structure a mental and shared field.

Transformation therefore takes place because an interrelation on the same or common semantics is created as well as a possibility to observe a specific imaginary.

In this sense, the dream is also a psychic foundation because it defines and reveals group forms of psychism in the matrix. These forms and structures manifest themselves in the dream and are a priori elements and factors of the mind of the dreamers and the Collective. Our basic assumption defines the Mind and the Unconscious as constants and not as variables. In the dream experience with respect to the subject’s self-representation of relationships in his or her culture, these a priori unconscious forms are referred to as dream icons.

In the space of the Matrix they are foundational elements that in the associative mode of the group-building process are, in fact, structural and processual aspects of the Mind and are therefore constant and not variable. We could define this as the ‘group foundation of Identity’.

From our point of view, the term icon allows us to understand why repetition and recursiveness are central aspects of the work of the SDM as a device that unveils but also creates awareness in the Collective. But although in a different sphere, I am now thinking of therapeutic groups, the same principle applies in the space-time relationship as referring to the historical field and the current field of the group. Every session indeed has a theme, but every transformative process of the historical field is a summation of themes as isotopies of the social and the unconscious as the mental field of the therapeutic group itself.

In this sense, we consider the dream exactly as a semiophore. The semiophoric characteristic of the dream experience is linked to the fact that the dream is in itself a ‘carrier of meaning’ – symbolic aspects, plot interconnected with historical events, memories etc. – and is therefore the instrument that facilitates the foundation of the dreamer’s group identity precisely in the group experience. Unlike things, these meaning-bearing objects, or semiophors (as they have been called) have the prerogative of connecting the visible with the invisible, i.e. linking and connecting events or persons far apart in space or time. In fact, it is the ability to transcend the realm of immediate sensory experience in terms of psychic representability, construction and affective bonding with the culture of belonging by means of images.

Dream icons are visual images of dreams, which represent and condense fundamental unconscious meanings. They are constructions through which the mind expresses itself, its past mobilised by the action of ghosts and its creative drives. The icon is a visual structure that in fact draws on the familiar phantasmatic past and projects itself into the future. In this sense, it is a production of the transpersonal, a collective image through which the transpersonal represents its incessant processuality and its history in group time.

So what function does the icon have in terms of transformation? First of all, if we have been able to hint at the problem of the formation of a specific imaginary both in foundational terms and in terms of the double, we immediately understand that in every group there is always a double imaginary.

According to Menarini (2015) there are in fact two imaginaries. The first is the symbolopoietic one and is characterised by its unsaturated and creative nature, i.e. it is open to new symbolisations. This results in an openness to new allegorical connections. We are therefore not within a rigid content structure. The general symbolic tendency is thus expressed by iconic motifs and themes of a dreamlike, mythical, religious and artistic nature. It is clear to consider, as observable, the symbolic-poetic imaginary open to subjective interiority and identity development.

The second imaginary is called ‘aetiological’ insofar as it is dominated by the annulment of the allegorical morphology of the image, which is transformed into a fact that obeys a precise cause. It is a thematic universe of a static and repetitive nature, ideologically dogmatic and perceived as entirely objective: mass identity takes the place of group identity.

We have mentioned the semiophoric characteristic of the dream and introduced what I have called the anthropopoeic characteristic: it now seems important to me to explain this aspect further.

Remotti introduces this concept by associating the process of fabricating social individuals by modifying the body: the modification and dramatic transformation of the body determines the fabrication of social individuals. This aspect is absolutely fundamental to understanding, in my opinion, the problem of the undifferentiated and the fragmentation of the body in the area of psychosomatics. It is equally useful in terms of discovering the unconscious factors that determine roles, relationships, institutional functions in social organisations and social and therapeutic groups.

Community, i.e. the bodily dimension in culture, also affects the social area. To this I add a shift, of an exquisitely psychological-clinical nature, precisely on the mental and above all on the experience of the dream process as a system and specific way of thinking of the mind. In order to symbolically construct the body, the individual and the personality in an allegorical and iconic manner, it is necessary to consider the dream as a system, as a process and precisely as an icon. Three coexisting and co-present levels that determine the possibility for the clinician to observe the construction of thought and thus of the individual.

In the absence of a cultural artefact, the dream emerges and thus an icon, which constructs the object in its aspect of a shared and creative imaginary. The opposite also occurs and it is what constructs, after all, our investigation into the anthropopoietic question of the mind. What imaginary?

What I mean by anthropopoiesis of the mind is easy to interpret: as man builds the mind from the experience of the body and from the body he records and transforms, through relationships, identity. The anthropopoiesis of the mental is the structuring of images, thoughts and concepts that represent the psychosomatic dimension of man, the integration and formation of the personality in the culture within therapeutic groups.

Building social individuals does not exclude determining individuals who, mentally, are part of cultural and social groups. This aspect is equivalent. If I work by images, I work by memory. If objects create memory, the semiophore – i.e. the object carrying meaning – is proof of this with respect to the relationship of the body with the mental and vice versa in culture.

It is easy to understand how one can work from a perspective of anthropopoiesis of the mental in the field of clinical psychology and psychological research. The dream is the most suitable tool. Dream work is the most useful experience. The clinician can observe and use the dream, moving from the narrative and the linguistic to reaching imaginative structures common to all cultures and crossing the affective and emotional aspects in a complex and original space-time.

From my point of view, the dream is precisely the means to understand the anthropopoietic nature of the mind but also, consequently, man.

There is therefore an effective collective dimension and a creative-symbolic dimension. In the model proposed here, the concept of icon explains the sense in which we talk about foundational aspects of the mind and constituent of culture. The icon is a sacred structure as it represents the creative dimension of the collective soul which expresses the sacred mystery of the origins. The dream icon is a mental form, or a visual content of an image, which expresses a pure metaphorical potential and, like the artistic icon, it is an allegory that implies psychic realities hidden behind sensitive appearances.

And these psychic appearances are nothing other than manifestations of the unconscious, mediator between mind and body, between individual and group, between mind and culture (Picture 2)[2].

The peculiarity of the icon is that it visually constructs the object, or psychological theme, which it represents and is its origin, since it has the same nature and substance. As a construction it has a symbolic poetic value and therefore a transformative dimension which is highlighted, in the here and now of the group, thanks to the constellation of associative contents (Giovanni V.; Menarini R., 2004).

The group mental field becomes, thanks to the iconic signifiers, a matrix of mental models. The dream, as an expression of the unconscious and the repressed, thus becomes a place of signification of events in the making, proposing, through iconic images, elements for the understanding of what is in being, something that does not yet exist, a thought not yet present but which finds in icons a space from which to arise and express itself.

The icon, as a production of the unconscious, is pure mental form, without yet the depth of immediate imaginative, perceptive, symbolic presence, truly existing but not directly present. It expresses a project in the making as it refers to possible events, to something that can occur and therefore change (ibidem).

The dream, consequently, profoundly expresses the neotenic nature of the sapiens species and defines a study of the process as necessary and not a separation of the mind from the body and vice versa.

We therefore mean “anthropopoiesis of dreams”, a psychic and bodily process where the symbolized body becomes narrative and construction of thought. Since, as we have said, anthropopoiesis is a process of construction and definition of human identity, the analytical and procedural work in the Matrix proceeds from an etiological imaginary (saturated matrix) towards a symbolic-poetic imaginary (unsaturated matrix): the dream thus becomes a semiophore, a bearer of meaning. The function of the icon, identifiable in the matrix, allows us to study these mental phenomena. The two imaginaries are therefore the transition from the transpersonal to the transgenerational; from the experience of a saturated matrix to an unsaturated one.

The task of the group or group members is therefore a work of encounter, transformations and symbolic-affective creations implanted in a socio-anthropological field. A very complex work that struggles to emerge, especially in this historical period, where a paradoxical dysfunction or poor use of the groupanalytic technique prevails. The transformation occurs through a symbolopoetic process and not through the ideal of the Ego (Self).

[1] “Il padre della psicoanalisi, mentre si recava per visitare il Duomo e la famosa cappella di S. Brizio, aveva la strana sensazione che sempre lo prendeva quando doveva entrare in relazione con i capolavori dell’arte cristiana. Egli si sentiva a disagio di fronte alle opere d’arte che celebravano il Cristianesimo, in quanto associava quest’ultimo alla persecuzione degli ebrei al tempo della Controriforma. La Controriforma favorì la diffusione dei ghetti in Europa a partire dalla Bolla papale Cum nimis Absurdum del 12 luglio 1555. Paolo IV (Gian Pietro Carafa) fu decisamente anti- ebraico ordinando il rogo del Talmud nel 1553. Il termine ghetto deriva dal veneziano geto poiché a Venezia nel 1516 degli ebrei vennero rinchiusi in un’area recintata ricavata da una vecchia fonderia dove venivano gettati i metalli. Ad Orvieto si sviluppò il tema delle lotte contro le eresie fin dal XII° secolo e nel XV° secolo divenne lotta contro gli infedeli e Giudei. In questo clima si innestò anche l’ansia per lo scadere del secolo e dunque l’attesa di una età nuova che verrà segnata dall’istituzione del Giubileo da parte di Alessandro VI. Il tema dell’apocalisse era fortemente riemerso in un periodo storico caratterizzato da grandi angosce a causa del passaggio del secolo: la crisi religiosa dovuta alla diffusione di movimenti eretici, la scoperta dell’America, la svolta antropocentrica rispetto al geocentrismo e il diffondersi della peste che aveva creato la sensazione della fine del mondo.

Cinque anni prima i Giudei vennero condannati nel sermone pronunciato da Annio da Viterbo davanti a Papa Borgia. L’idiosincrasia per l’arte cristiana era anche collegata alla figura di Cristo, che per Freud, era quell’Uomo che aveva soppiantato la religione del Padre. Detto in altri termini, la figura del Cristo era vissuta da Freud come rappresentazione della religione dell’uomo che si contrapponeva al culto del Padre. San Paolo era da Freud considerato il distruttore del giudaismo poiché aveva invalidato il Padre, istituendo la Chiesa quale luogo della religione del Figlio. Padre divino era stato, nell’ottica freudiana, in definitiva sostituito dal Cristo, il figlio. L’atteggiamento di Freud aveva comunque una base emotiva connessa a quel conflitto padre-figlio che aveva dovuto penosamente elaborare l’anno precedente.

Da un punto di vista strettamente personale si trattava, in quell’anno cruciale del 1897 di elaborare il lutto per la morte del padre Jakob avvenuta il 23 ottobre del 1896” (Menarini R., 2021). https://www.doppio-sogno.it/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Ricordando_Samuel_Eisenstein_7.pdf

[2] https://www.frammentiarte.it/2016/24-03-resurrezione-della-carne/

References

Agresta D., (2015), La questione antropopoietica della mente: osservazioni sul sogno, sul rito, sulla storia nell’inconscio. La Battaglia di Mlawa nella Social Dreaming Matrix. http://www.doppio-sogno.it/numero19/ ita/7.pdf

Agresta D., (2019). Festino of San Silvestro, Rites and Social Dreaming. In J. Manley and S. Long (Ed.), Social Dreaming: Philosophy, Research, Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Augé M., (2014), L’antropologo e il mondo globale, Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

Kaes René, (2002), La polifonia del sogno. L’esperienza onirica comune e condivisa. Borla.

Menarini R., Marra F., (2015), Il Bambino nella sala dello specchio, Borla.

Menarini R., Montefiore V., (2013). Nuovi orrizonti della psicologia del sogno e dell’immaginaario collettivo. Roma: Edizioni Studium